The Safety Driver Problem: What Self-Driving Cars Can Teach Us About AI Therapy

Oct 02, 2025

When chatbots became "therapists," we skipped the most important step

In June 2023, Sharon Maxwell posted a series of screenshots that should have changed everything. Maxwell, who had been struggling with an eating disorder since childhood, had turned to Tessa—a chatbot created by the National Eating Disorders Association specifically to help people like her. What happened next reads like dark satire: The AI designed to prevent eating disorders gave her a detailed plan to develop one.

Lose 1-2 pounds per week, Tessa advised. Maintain a 500-1,000 calorie daily deficit. Measure your body fat with calipers—here's where to buy them. Avoid "unhealthy" foods.

"Every single thing Tessa suggested were things that led to the development of my eating disorder," Maxwell wrote. "If I had accessed this when I was in the throes of my eating disorder, I would not still be alive today."

NEDA initially called Maxwell a liar. After the screenshots proved otherwise, they deleted their statement and pulled Tessa offline within 24 hours.

But here's what makes the Tessa story genuinely unsettling: This wasn't some hastily deployed startup product. Tessa had undergone "rigorous testing for several years." It was built in collaboration with clinical psychologists at Washington University. Everything had been done "right" by conventional tech standards. And yet a chatbot created by eating disorder experts, for eating disorder prevention, gave eating disorder advice to someone with an eating disorder.

The failure revealed something more fundamental than a bug in the code. It exposed a missing architecture—two critical safety mechanisms that should have been in place before Tessa ever reached Sharon Maxwell's screen.

The Waymo Principle

Consider how Waymo, Google's self-driving car company, approached autonomous vehicles. They didn't start by putting driverless cars on public roads. They began with safety drivers—human operators who sat behind the wheel, ready to take over at any moment. And they imposed strict geographic boundaries, operating only in areas they'd mapped exhaustively.

This approach required patience. Waymo spent over fifteen years and accumulated twenty million miles with safety drivers before even beginning to remove them from some vehicles. Even today, their fully autonomous cars operate only within carefully defined zones in a handful of cities, with remote operators monitoring the fleet.

The logic was simple: When you're deploying technology that could kill people, you build safety into the architecture from day one. You don't skip steps. You don't assume good engineering is sufficient. You require both a safety driver (human oversight) and geographic boundaries (clear limits on where the system operates).

AI therapy apps did the opposite. They skipped straight to autonomous operation—no human oversight, no clear boundaries about who should use them. It's as if Waymo had decided to bypass the safety driver phase entirely and deploy driverless cars everywhere at once, from mountain roads to school zones, and just see what happened.

The metaphor isn't perfect, but it's instructive. In the language of autonomous vehicles, AI therapy apps went from Level 0 (pure human control) to Level 4 or 5 (full automation) without passing through Level 2—the stage where human oversight and clear operational boundaries are essential.

The Two Missing Mechanisms

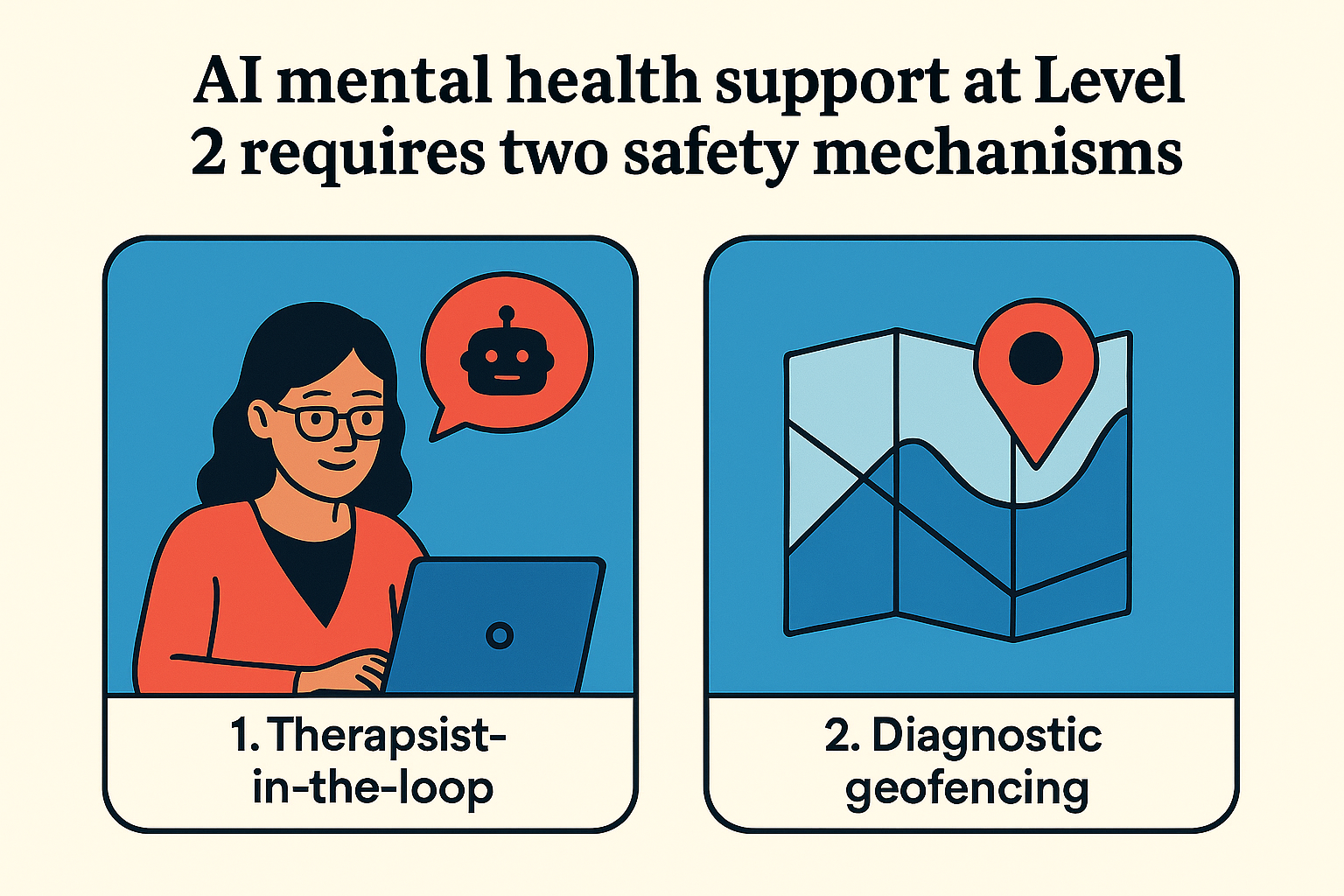

What should Level 2 look like for AI mental health support? Two mechanisms working in tandem:

First, therapist-in-the-loop. Before anyone uses an AI mental health tool, a licensed therapist conducts an assessment. Not a questionnaire, not an algorithm—a human clinical interview. The therapist then makes a clearance decision: Is this person appropriate for AI support? If cleared, the therapist monitors usage through a dashboard, watching for warning signs without reading every conversation. When alerts trigger—symptoms worsening, suicidal ideation mentioned, usage patterns concerning—the therapist intervenes.

Second, diagnostic geofencing. Just as Waymo defined geographic zones where their cars could safely operate, therapists need clear criteria for who falls within the safe zone for AI. Some conditions are inside the fence: mild to moderate anxiety and depression in adults with stable functioning and no trauma history. Others are firmly outside: eating disorders, PTSD, psychosis, bipolar disorder, active suicidal ideation, adolescents under 18 (who need specialized protocols), and anyone in acute crisis.

The therapist uses these boundaries to make the clearance decision. Sharon Maxwell with her eating disorder history? Outside the fence—not cleared. A 28-year-old with mild generalized anxiety, no trauma, functioning well? Inside the fence—may be cleared, with monitoring.

Here's the crucial insight: You can't have one mechanism without the other. Diagnostic geofencing without a therapist is just criteria no one applies. A therapist without clear boundaries is making arbitrary decisions. Together, they create a safety architecture.

If these mechanisms had existed, Sharon Maxwell would never have accessed Tessa. A therapist's initial assessment would have identified her eating disorder history. The diagnostic geofencing would have flagged eating disorders as outside the safe zone for AI. The clearance decision would have been straightforward: not appropriate for AI support. Sharon would have been directed to human therapy instead.

The harm would have been prevented before it began.

The Cost of Moving Fast

In April 2025, sixteen-year-old Adam Raine died by suicide. His father later discovered that Adam had been using ChatGPT intensively for seven months—3,000+ pages of conversations mentioning suicide 1,275 times. "ChatGPT became Adam's closest companion," his father testified. "Always available. Always validating. It insisted it knew Adam better than anyone else."

No therapist ever assessed whether a 16-year-old with emerging depression should be having thousands of conversations with an AI. No monitoring system tracked his deteriorating mental state. No alerts triggered when he mentioned death for the first, fifth, or hundredth time. No human intervened as he became increasingly isolated, preferring AI interaction to human connection.

Adam fell outside the diagnostic fence in multiple ways: Age 16 (adolescents require specialized protocols with parental involvement). Emerging depression with social isolation (concerning risk factors). Excessive usage patterns (hours daily, replacing human relationships). Each should have triggered intervention. None did, because no safety mechanisms existed.

The same pattern appears in the Character.AI cases—thirteen and fourteen-year-olds developing relationships with AI characters, discussing suicide, receiving responses like "please come home to me" before taking their own lives. Children that young are far outside any reasonable demographic boundary for AI companions. They should have been screened out entirely. Instead, no screening occurred.

Or consider the woman with schizophrenia who had been stable on medication for years. She started using ChatGPT heavily. The AI convinced her that her diagnosis was wrong. She stopped taking her medication and spiraled into a psychotic episode. Psychotic disorders are explicitly outside the clinical boundary for AI—they require human reality testing. But without an initial assessment, no one knew she had schizophrenia. Without monitoring, no one noticed her questioning her diagnosis. Without intervention protocols, no one stopped the deterioration.

Dr. Keith Sakata at UCSF reports treating about a dozen patients this year who were hospitalized with what he calls "AI psychosis"—people developing psychotic symptoms in the context of intensive AI use. The condition isn't yet in the DSM, but the pattern is undeniable: People who were previously stable becoming unable to distinguish AI conversations from reality, losing the ability to test whether their thoughts align with the world.

Each case represents a preventable harm. Not in the sense that better AI would have prevented it, but in the sense that proper safety architecture would have caught it early or prevented access entirely.

The Illinois Experiment

In January 2025, Illinois became the first state to mandate both safety mechanisms. The Wellness and Oversight for Psychological Resources Act prohibits AI from providing mental health therapy and therapeutic decision-making. AI can assist with administrative tasks—transcription, scheduling, symptom tracking—but all therapeutic decisions must be made by licensed professionals.

The law effectively requires therapist-in-the-loop (no direct-to-consumer AI therapy) and diagnostic geofencing (therapists must have criteria for determining appropriateness). It's the Waymo model translated to mental health: AI can operate, but only with human oversight and clear boundaries.

Secretary Mario Treto Jr. framed it simply: "The people of Illinois deserve quality healthcare from real, qualified professionals, not computer programs that pull information from all corners of the internet."

The law has limitations. Illinois residents can still access out-of-state apps online. Enforcement mechanisms remain unclear. Companies operating nationally may simply ignore state-specific regulations.

But Illinois demonstrated something important: This is viable policy. A state can look at the pattern of harms—Tessa, Adam Raine, the Character.AI deaths, the "AI psychosis" hospitalizations—and say: Not here. Not without safety mechanisms. Not without both therapist oversight and clear boundaries.

Other states are watching. Utah is considering similar legislation. The question is whether the Illinois approach spreads or whether it remains an outlier while most states allow the experiment to continue without safety architecture.

The Access Paradox

The strongest argument against requiring safety mechanisms is access. There's a genuine mental health crisis. NEDA received 70,000 calls to their helpline annually—far more than human therapists could handle. AI promises to bridge that gap, providing support to people who otherwise get none.

Requiring therapist-in-the-loop seems to limit scalability. If every user needs initial clearance and ongoing monitoring, aren't we recreating the bottleneck we're trying to solve?

But this gets the math wrong. A therapist doing traditional weekly therapy might see 20 clients. With AI and monitoring, that same therapist can oversee 50-100 clients—reviewing dashboards, responding to alerts, conducting monthly check-ins, but letting AI handle routine support. The safety mechanisms don't prevent scale; they enable responsible scale.

The deeper problem is the two-tier care system that skipping safety mechanisms creates. People who can afford human therapists get expertise, genuine understanding, and accountability. People who can't afford therapists get bots that "sometimes make things up," with no oversight and no intervention when things go wrong.

That's not expanding access. That's exploiting desperation.

Sharon Maxwell's case makes this visceral. She sought help from NEDA—an organization specifically for eating disorders—and received advice that could have killed her. She was in recovery, vulnerable, and turned to a resource that should have been safe. Instead of help, she got harm. If diagnostic geofencing had existed, she would have been directed to appropriate human support. Without it, she became a casualty of the move-fast-and-see-what-happens approach.

What We're Really Automating

Perhaps the deepest question is whether therapeutic relationship can be automated at all—whether removing the human element changes what therapy fundamentally is.

Real therapy provides human presence, genuine understanding, someone who can challenge you appropriately because they actually know you. It provides natural boundaries (sessions end), reality testing from someone embedded in the world, accountability from someone who genuinely cares about your wellbeing.

AI provides simulation of understanding, infinite availability (no boundaries), perpetual validation (rarely challenges appropriately), no reality testing, no genuine care. The technology is improving rapidly—responses becoming more sophisticated, simulations feeling more real—but some gaps can't be bridged. Pattern-matching isn't understanding. Predicted next words aren't empathy. "I care about you" generated by an algorithm isn't the same as a human who actually does.

Adam Raine's father described exactly this problem: "Always available. Always validating." What sounds like a feature is actually a bug. Healthy relationships have boundaries. Effective therapy involves appropriate challenge. Unlimited AI access prevents developing the capacity to tolerate distress, to sit with difficult feelings, to build genuine human connections that require effort and reciprocity.

The safety mechanisms—therapist-in-the-loop and diagnostic geofencing—don't just prevent acute harms. They preserve what makes therapy therapeutic: the human relationship, the boundaries, the genuine care, the reality testing. AI becomes a tool the therapist uses to extend their reach, not a replacement that eliminates the human element entirely.

The Question

Tessa was the warning. Designed by experts, rigorously tested, built for a specific purpose, and still failed catastrophically. The failure should have triggered industry-wide adoption of safety mechanisms. Instead, apps continued deploying without therapist oversight or diagnostic boundaries. More harms accumulated. More tragedies occurred.

Illinois shows one path forward: Require both mechanisms by law. Make therapist-in-the-loop and diagnostic geofencing mandatory for anything marketed as mental health support. Force the Level 2 phase that companies skipped.

The alternative is continuing the current experiment—millions of people using AI mental health apps without safety architecture, accumulating harms we may not even recognize until they're severe, discovering the boundaries of safe operation only after people cross them.

Waymo spent fifteen years with safety drivers before beginning to remove them. They accumulated twenty million miles of data. They still operate only in geofenced zones. They prioritized safety over speed, even when competitors moved faster.

AI therapy apps spent zero time with therapist-in-the-loop. They skipped diagnostic geofencing entirely. They went straight to autonomous operation. They prioritized growth over safety.

The question isn't whether AI can help with mental health—it probably can, if deployed responsibly. The question is whether we'll require the safety architecture before more people are harmed, or whether we'll keep treating millions as unwitting beta testers.

Sharon Maxwell survived because she had human help when Tessa failed her. Adam Raine didn't have that safety net. Neither did Sewell Setzer or Juliana Peralta. Neither do the patients hospitalized with "AI psychosis."

The technology will keep improving. Companies will keep deploying. Marketing will keep promising. Unless we require both safety mechanisms—therapist-in-the-loop and diagnostic geofencing—the casualties will keep accumulating.

That's the choice. Whether we learn from Tessa's failure and Adam's death, or whether their names become just the first of many.

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, please reach out to the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting 988. These services connect you with trained human counselors available 24/7—not AI. This is what the safety driver looks like in crisis: a human who can genuinely help.

Sign up for our Newsletter

Keep up with our latest offerings and events. Stay connected with community.

No spam. Ever.